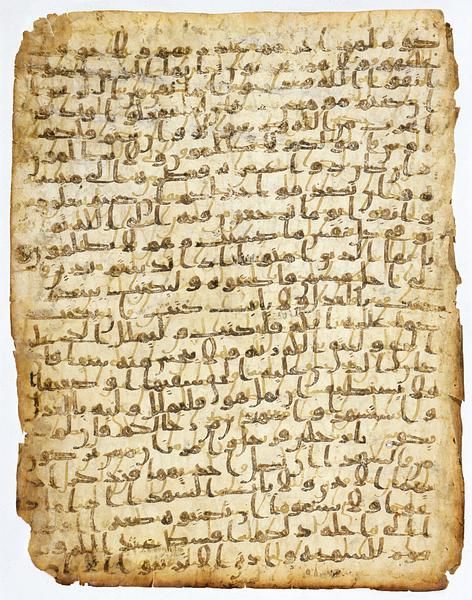

This leaf is a fragment from one of the oldest extant copies of the Koran. It is a palimpsest: the original text was scraped off and a new one was written on the parchment. In time, the original text reemerged and now can be read as a shadow under the later one. Both are transcripts of the Koran’s sura 2, “The Cow.”

In Islam, the Koran was revealed direct from God to Muhammad through the archangel Gabriel, and its words were memorized by the Prophet’s followers. When the Koran was written down shortly after the Prophet’s death, minor variations were found in the different copies. According to tradition, the third caliph, Uthman (644-656), is the one who once and for all decided which text was correct – the one we know today. All variants with even the most insignificant divergences from the authorized text were destroyed, so that there would be no dissent about God’s commandments to the believers. While the lower text is a copy of a pre-Uthman text, the upper one is identical to that in the authorized Koran.

Both texts were written in Hijazi, the earliest Arabic script used for Korans and the one that was used in Mecca when the Islamic expansion got under way in earnest.

Inv. no. 86/2003

Published in:

Sotheby’s, London, 22-23/10-1992, lot 551;

Francois Déroche [et al.]: Manuel de codicologie des manuscrits en écriture arabe, Paris 2000, cat.no. 11;

Christie's, London, 1/5-2001, lot 12;

Ramsey Fendall: Islamic calligraphy, Sam Fogg Rare Books and Manuscripts, London 2003, cat.no. 1;

Alba Fedeli: “Early evidences of variant readings in Qur’ânic manuscript” in Karl-Heinz Ohlig and Gerd-R. Puin (eds.): Die dunklen Anfänge : Neue Forschungen zur Entstehung und frühen Geschichte des Islam, Berlin 2005, pp. 3-25;

Marcus Fraser and Will Kwiatkowski: Ink and gold : Islamic calligraphy, ed. Gemma Allen, London 2006, pp. 14-17;

Alain George: The rise of Islamic calligraphy, London 2010, p. 32, fig. 13;

Marcus Fraser: “The earliest Qur’anic scripts” in Margaret Graves (ed.): Islamic art, architecture and material culture : new perspectives, Oxford 2012, p. 124, fig. 4;

Institute of Ismaili Studies: Muslim Societies and civilisations, Student reader 1, London 2013, p. 112;

Francois Déroche: Qur'ans of the Umayyads: a first overview, Leiden 2014, p. 153, Codex Sana’a, I;

Keith E. Small and Francesca Leoni: Qur'âns : books of divine encounter, Oxford 2015, pp. 9-10, 16-17;

Alain George: “The Qur’an, calligraphy, and the early civilization of Islam” in Finbarr Barry Flood, Gülru Necipoglu (eds.): A companion to Islamic art and architecture, B. 1, From the Prophet to the Mongols, Hoboken 2017, p. 114, fig. 4.1;

Angelika Neuwirth: “The 'Discovery of writing' in the Qur'an : tracing a cultural shift in Arab late antiquity” in Nuha Alshaar (ed.): The Qur’an and adab : the shaping of literary traditions in classical Islam, Oxford 2017, fig. 1, pp. 64-65;

Manar Hammad: L’instauration de la monnaie épigraphique par les Omeyyades, Paris 2018, fig. 20, p. 20;

Stig T. Rasmussen: Klassisk arabisk litteratur i oversættelse til dansk: en litteraturhistorisk vejvisende antologi, København 2018, pp. 20-21;

Ekhtiar, Maryam D.: How to read Islamic calligraphy, New York 2018, fig. 31, p. 71;

Deniz Kitir: Klassisk og moderne islam, 2. ed., Aarhus 2020, p. 35;

Sheila S. Blair and Jonathan M. Bloom: “The Islamic world” in James Raven (ed.): The Oxford illustrated history of the book, Oxford 2020, fig. 1, p. 197;

Joachim Meyer, Rasmus Bech Olsen and Peter Wandel: Beyond words: calligraphy from the World of Islam, The David Collection, Copenhagen 2024, cat. 1, pp. 116-117;

Rasmus Bech Olsen: “Beyond words: calligraphy from the World of Islam”, Orientations, 55:4, 2024, fig. 2, p. 35;