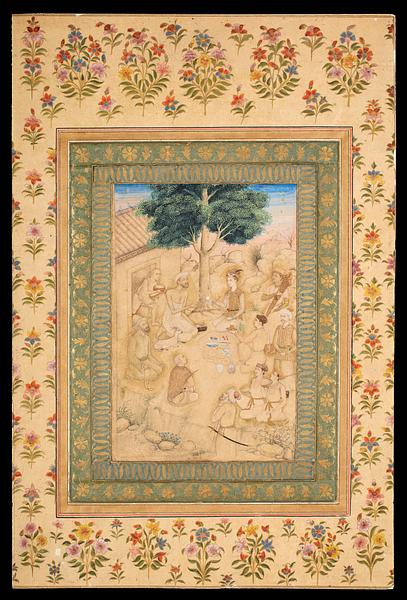

The painting depicts the meeting between two worlds – the spiritual and the secular. The spiritual is shown on the left side of the painting, where an elderly, thin ascetic is kneeling in front of his simple residence surrounded by three disciples. Two of them, especially, are simply clad and clearly do not value material goods. The protagonist is holding a book in one hand; one disciple is holding a rosary, another disciple an armrest used for meditation, while he has a beggar’s bowl and a knife in a rope around his waist. The youngest disciple is bringing a wooden bowl with food or drink from the house.

The right side is dominated by an elegantly clad young prince and six of his courtiers, one of whom is carrying his sword wrapped in a magnificent cloth, two are attendants with swords and daggers in their belts, two are musicians, and one is a servant who has just laid out a meal served on costly blue-and-white dishes and with drinks in elegant glass decanters.

The contrasts are striking but free of conflict. There is respectful contact between the two groups. Depictions of princes, both those who can be identified and those who cannot, as is the case here — shown with holy or learned men were common in India from the end of the 16th century and far into the 17th, as well as later. (See also

15/2016.) They are visualizations of the secular world’s respect for the spiritual and in this period often crossed religious lines, though here we see only Muslim holy men: Sufis.

The painting is characterized by manifest naturalism and can tentatively be attributed to the artist Manohar (active from 1582 to c. 1624). The faces are expressive and the prince’s vest of woven, figurative silk is reproduced with a wealth of details. Its motif with confronted couples in a landscape brings to mind Persian silks of the period (see

29/2008), while the tiger on the hunt reveals the cloth’s Indian origin, unless the painter used his artistic creativity.