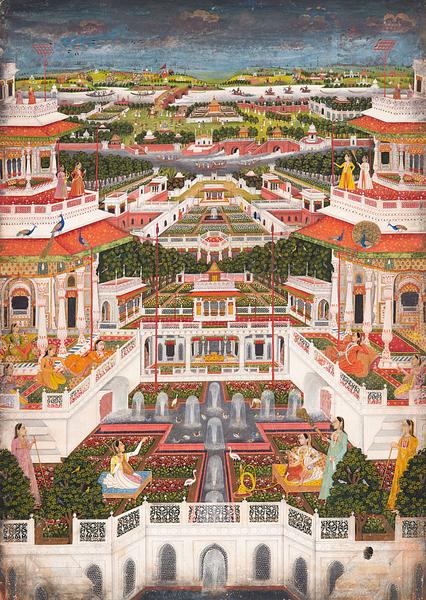

The miniature, whose primary motif is a fantastic palace complex populated by a prince’s concubines along with their female servants and guards, in a way depicts the world as one great garden. In the distance we see the prince on the back of an elephant, and on the other side of the river all manner of activities are taking place that form a powerful contrast to the perhaps pleasant but enforced idleness of the women of the harem.

The painting has been attributed to Faiz Allah, one of the many skilled artists who worked in the growing provincial courts at the time when the Mughals’ power was waning. He was familiar with the concept of European linear perspective, but he disregarded its laws, either deliberately or unintentionally.

Inv. no. 46/1980

Published in:

Marie-Christine David and Jean Soustiel: Miniatures orientales de l'Inde, 3, Galerie Jean Soustiel, Paris 1983, p. 47;

Stuart Cary Welch: India: art and culture 1300-1900, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1985, cat. 186;

Kjeld von Folsach: Islamic art. The David Collection, Copenhagen 1990, cat. 52;

Attilio Petruccioli (ed.): Il giardino islamico: architettura, natura, paesaggio, Milano 1994, p. 112;

Kjeld von Folsach, Torben Lundbæk and Peder Mortensen (eds.): Sultan, Shah and Great Mughal: the history and culture of the Islamic world, The National Museum, Copenhagen 1996, cat. 206;

Kjeld von Folsach: Art from the World of Islam in The David Collection, Copenhagen 2001, cat. 82;

Fantasies de l'harem i noves Xahrazads, Centre de Cultura Contemporania, Barcelona 2003, p. 45;

Steen Estvad Petersen: Drømmen om Paradiset: islamisk havekultur, Valby 2005, p. 343;

Kjeld von Folsach: For the Privileged Few: Islamic Miniature Painting from The David Collection, Louisiana, Humlebæk 2007, cat. 129;

Kjeld von Folsach: Flora islamica: plantemotiver i islamisk kunst, Davids Samling, København 2013, cat. 5;

Adam Barkman: Making sense of Islamic art and architecture, London 2015, pp. 96-97;

Monica Juneja: “Circulation and beyond: the trajectories of vision in early modern Eurasia” in Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, Catherine Dossin, and Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel (eds.): Studies in art historiography: Circulations in the global history of art, Farnham 2015, p. 64;

Kjeld von Folsach: “Paradise on earth: water and the Islamic garden”, in John Kuhlmann Madsen, Nils Overgaard Andersen og Ingolf Thuesen (eds.): Water of life : essays from a symposium held on the occasion of Peder Mortensen's 80th birthday, p. 184-195, Copenhagen 2016, fig. 3;

Amita Baig og Rahul Mehrotra: Taj Mahal: multiple narratives, New Delhi 2017, p. 113;

Kjeld von Folsach, Joachim Meyer: The Human Figure in Islamic Art – Holy Men, Princes, and Commoners, The David Collection, Copenhagen 2017, cat. 61;

Ira Mukhoty: The lion and the lily: the rise and fall of Awadh, New Delhi 2024, ill. 12 og s. 105;

Corinne Lefèvre, Jean-Baptiste Clais (eds.): Les arts moghols, Paris 2024, fig. 464, pp. 448-449;

Farhad Kazemi, Monique Buresi (eds.): Jardins et palais d'Orient, Milano 2024, ill. 1, pp. 80- 81;